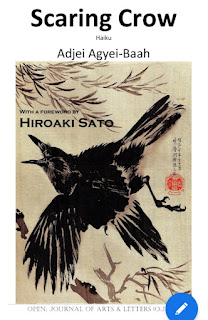

This blog features an interview with Ghanaian poet Adjei Agyei-Baah, one of the leading writers of “Afriku,” the school of haiku poetry flourishing in Africa. Agyei-Baah is the author of three volumes of haiku: his latest, Scaring Crow (Buttonhook Press); Afriku (Red Moon Press); and Ghana 21 Haiku (Mamba Africa Press). He is the cofounder of the Africa Haiku Network (AHN) and coedits Mamba Journal, Africa’s first haiku magazine.

|

| Adjei Agyei-Baah |

Could you talk a little bit about the history of haiku writing in Africa?

Haiku writing in Africa owes a lot to Sono Uchida, the prominent Japanese haiku poet and diplomat, who thirty years ago in Senegal initiated a haiku contest in the French language. That was the first international haiku competition in Africa.

During his mission as a Japanese ambassador in Africa, Uchida always felt that Senegal would be a fertile ground for the growth of haiku. The way the Senegalese people adapted to nature reminded him of the traditional world of the Japanese people, a way of life that was rapidly disappearing. According to Sono Uchida, it was the belief of haiku poets in Japan that nature does not belong to humanity, but rather it is humans who belong to nature.

Uchida’s promotion of haiku in Senegal was supported by the first President of Senegal, His Excellency Léopold Sédar Senghor, who was also a great friend of haiku.

In more recent years, haiku has spread particularly in West Africa, especially in Ghana and Nigeria. Some African haiku writers have pushed the genre in new directions. Emmanuel-Abdalmasih Samson of Nigeria, for example, invented what he termed “mirror haiku,” a technique now used by many other haiku writers around the world. Here’s an example from Samson’s poetry:

walking in the rain

umbrellas sing counterpoint

August concerto

August concerto

umbrellas sing counterpoint

walking in the rain

How did you personally come to haiku as a form for your poetry? Why does haiku particularly appeal to you as a writer?

I got to know haiku through my fellow Ghanaian countryman, Nana Fredua-Agyeman, a very strong haiku contender. He used to share haiku on his blog. I followed his adventures and became addicted to the genre. I was captivated by its feature of brevity and the way a short haiku also says much more. It seemed a good way to tell African stories.

Your new chapbook, Scaring Crow, has a remarkable form—every haiku mentions a scarecrow. What drew you to that image, and what associations does it have for you personally and as an artist?

It's a book I wrote purposely to try to push the frontiers of haiku. Arguably, it's the first haiku collection ever to explore a single theme in more than 100 ways. It was an honour and privilege to have great haiku scholars and doyens like Hiraoko Sato, Professor John Zheng, and Scott Mason contributing the foreword and blurbs.

Yes, I began with longer poems before discovering haiku, and I’ve had several long poems published in international journals and anthologies. As part of my practice, I create a haiku when nature presents a moment in a flash of lightning, that delivers a lasting after-image. But when I want to address humanity, or talk about more scholarly topics, I usually write longer poems.

Any advice for writers who would like to write haiku?

Deep observation yields haiku! To communicate an aha! moment from nature, a novice writer must constantly observe. Read good haiku journals and publications to improve your craft. I hope to see more African poets, both young and experienced, come to the practice of haiku to tell African stories, as few are doing at the moment.

Here are some favorites of mine from Adjei Agyei-Baah’s new chapbook, Scaring Crow:

All Saints’ Day

a scarecrow glows

in fireflies

gleaning the field

a hidden melon

behind the scarecrow

ripened field

an old scarecrow invites

birds to party

flitting butterfly

the scarecrow’s shoulder

provides a rest

country walk…

passing on an old hat

to a scarecrow

parting mist…

the open arms

of a scarecrow

Zack’s most recent book of poems, Irreverent Litanies

Zack’s most recent book of translations, Bérenice 1934–44: An Actress in Occupied Paris

Other posts of interest:

Getting the Most from Your Writing Workshop

How Not to Become a Literary Dropout

Putting Together a Book Manuscript

Does the Muse Have a Cell Phone?

Poetic Forms: Introduction, the Sonnet, the Sestina, the Ghazal, the Tanka, the Villanelle

No comments:

Post a Comment