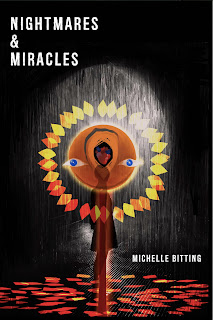

This blog is an interview with the writer Michelle Bitting, whose book Nightmares & Miracles, winner of the Two Sylvias Press Wilder Prize, establishes her as an important voice in poetry.

|

| Poet Michelle Bitting |

Michelle Bitting: When writing, we all experience the “eternal return” to childhood matters—memories, sensory impressions, snippets of recollected gesture and dialogue. As a writer, I’ve been working through a fair amount of trauma and dysfunction from the distant past since I started making poems a couple decades ago.

To be blunt and to the point: twenty-five years after my older brother William committed suicide, my younger brother John took his life as well. This latest tragedy occurred in December of 2019, the day after Christmas, and at our parents’ house. In attempting to get at the molten center of that, I’m also trying to free myself from it, or at least transform it into song outside myself. I’m not sure I’d still have the passion and joy for life I hold now if I hadn’t surrendered to this activity, which feels almost mystical to me. When I lost my younger brother by suicide recently, it was (again) a terrible, shocking thing. I had to don the mask and suit and absurd flippers and dive back down.

Q. One of the poems in your collection is titled, “A Poet Embraces the Darkest Hour.” To me, that could be a description of this whole book. What is it that a writer gains by embracing the darkest hour?

Wouldn’t it be great if we didn’t have to keep embracing the darkest hour? I would really love that. I think we could all use a grand break, don’t you? Along with each personal trial (and mine, in relation to the wide world of suffering humans are bearable by comparison) it feels, of late, like a constant barrage of outrageous torments chipping away at our collective serenity. And sanity! But on we endure, and I try to expand beyond my particular suffering into new articulations that have to do with making stories, or mythologizing, if you will. Crawling through the tunnels with my flashlight I find stuff that glows and helps me figure my way forward. I remember I’m a dot in time puzzling the “facts” and past into something that helps me embrace the chaos while also organizing it in a way through language, image, sound. To state the obvious, and to quote Carl Jung: “There is no light without shadow, and no psychic wholeness without imperfection.”

The “flip side” of the nightmare portion of life, the sense of “miracle” is often the glorious, astonishing feeling of having survived horrible derangements and despair—the terror of what came before. I know this sounds awfully dramatic, but having experienced a fair amount of violence, sustained psychological stress, and volatility in my family environment (s) over the years, making it through those passages delivers a euphoria, a deep gratitude and delight in the smallest “things” that are often of the spirit and not necessarily concrete. We may be battle-weary and scarred, but we’re still mighty. We get excited about life and art because these engagements are precious and necessary. Just as death is necessary. Look, I’ll never be over losing my brothers or our dog Charlie, among other brutal realities and epic failures I have to contend with in myself, my family, the world at-large. Shaping a little container of words on the matter is a positive gesture that helps soften the blow even if it hurts in the writing and remembering.

Q. Your book deals in part with the roles of women in your mother’s generation and your own. Do you see continuity or discontinuity in how the women of those two times dealt with issues of parenting and relationships?

This is a question I’m actively attempting to answer, and perhaps reconcile, in my mind and in my writing. And it connects to what we’re experiencing on the national and global levels of society, history, politics, and more. How do we “break down” and break away from the mistakes of the past, and find ways to heal, change, and forgive forward?

A major point of contention seems to be the ongoing lack of admission of wrongs done, and poor choices that continue to be made that hurt and subjugate people. At this point, I’m most concerned for the rising generations, the young people who have to somehow move valiantly into the future dragging a behemoth of economic and environmental problems that are complex, yes, but also perpetuated by older generations who continue to make greedy and heinously controlling decisions that serve their own immediate desires but certainly not the true prosperity and freedom of future generations—or civilization, for that matter.

And yet, without compassion and understanding for each other and the faults of those who came before, what are we? This predicament feels especially critical and troubling at this time of turbulent change. Well, we’re not the first to struggle through dark times. The best we can do is keep singing.

Q. Could you talk about how you are moving forward from this gripping collection of poems?

I’ve embarked on a “larger” and ongoing hybrid (fiction, memoir, script, poetry) writing project that involves my great-grandmother, the remarkable stage and screen actress Beryl Mercer. She was quite a renowned character performer of the 1930s, and considering obstacles she endured to become who she was, a feminist exemplar. I’m channeling her and imagining into various roles together as we investigate family and societal ills, as well as achievements and ongoing patriarchal damage spanning a century. For me, this is a major creative undertaking—in this case, that’s an appropriate word!

Here's one of my favorite poems from Michelle Bitting’s new collection:

The Unmaking

Where brightness goes to die

after years of settling its joy in our lap

the husk of all we prized and carried

just as my son clutched that four-pawed warmth

in his hope-stripped hands

surrendering our furry bundle

in an old blue baby blanket

Dachshund-Beagle-Chihuahua mutt

the dwindling fruit of his ruined heart

driven to the mercy hotel in the dead of night

because this suffering we could no longer abide

and so passed on to the doctor

at the all-hours clinic

a kind, white-coated vet who nodded

a solemn You’re doing the right thing

after I stammered Maybe a different medicine?

the twin neithers of her eyes meeting mine

silence dropping its dirty oars

breaking the human surface

rowing us closer

Who asks for this?

my son’s beggared hand finding me

our palms’ salt rivers twining

reading each other

our runned-over prayer

completing the circle

as we turned to find the door, the lot, our keys, our car

our way home in a vacant dark

of dreaming streets

first pocketing his collar, some paperwork

how sweetly he looked at us

as the last light left

Zack’s most recent book of poems, Irreverent Litanies

Zack’s most recent book of translations, Bérenice 1934–44: An Actress in Occupied Paris

Other posts of interest:

Getting the Most from Your Writing Workshop

How Not to Become a Literary Dropout

Putting Together a Book Manuscript

Does the Muse Have a Cell Phone?

Poetic Forms: Introduction, the Sonnet, the Sestina, the Ghazal, the Tanka, the Villanelle