The

last approach to being an American writer that I’d like to discuss is the

satirist or the critic. These writers do engage

directly with the American mainstream, unlike the expatriate or the internal

exile, for instance. But the critics and satirists paint the United States in

order to hold up a mirror and show the blemishes, often to hilarious effect.

I’d

say the best known U.S. writer satirist/critic is Mark Twain, who had an

uncanny ability to mimic the speech and the foibles of the common man or woman.

One

of my favorite parts of Twain’s The

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn is his portrayal of Tom Sawyer’s gullible

Aunt Sally. Aunt Sally is trying to figure out how the leg of the bed in Jim’s

prison was sawed off, when Jim was locked in a room with no saw. In reality,

Tom Sawyer did the sawing—is that a pun? Here is Aunt Sally’s description of

the situation:

“You may well say it, Brer Hightower! It’s jist as I was a-sayin’ to Brer

Phelps, his own self. S’e, what do

you think of it, Sister Hotchkiss, s’e? Think o’ what, Brer Phelps, s’I? Think o’ that bed-leg sawed off that a

way, s’e? think of it, s’I? I lay it never sawed itself off,

s’I—somebody sawed it, s’I; that’s my opinion, take it or leave it, it mayn’t

be no ’count, s’I, but sich as ’t is, it’s my opinion, s’I, ‘n’ if any body k’n

start a better one, s’I, let him do it, s’I, that’s all.”

What

a gift for rendering the Mississippi Valley dialect Twain had! As much as Twain makes fun of the common

man and woman, though, and the gullibility of Americans, you do get the sense that

he is in some ways a populist. His poking fun is often done out of a democratic

impulse to nudge the masses toward greater awareness, and not out of a deeper

cynicism about the U.S.

Other notable American satirists or critics:

On

the poetry side, Edward Arlington Robinson, author of “Miniver Cheevy.” Robinson had a knack for finding the underside of different fates.

e.e.cummings, particularly in poems such as “pity this busy monster, manunkind,” showed the materialistic and insensitive face of U.S. society.

On

the fiction side, Sinclair Lewis, a novelist whose work was extremely important

for my parents’ generation. Lewis, one of the few Americans to win the Nobel

Prize for Literature, is not read as much today as he was two generations ago,

but he produced some scathing satires of small-town American life, including

the novels Babbitt and Main Street. His dystopian fiction about

fascism taking over an all-American community, It Can’t Happen Here, published in 1935, might well be a prophetic

glimpse at the regional surge of extreme right politics outside of urban

America.

|

| Sinclair Lewis, author of It Can't Happen Here and other novels |

NathanaelWest, author of Miss Lonelyhearts, mocked the shallowness of popular American culture.

I

think some of the recent American women novelists are critics of American

society, such as Jane Smiley, author of A

Thousand Acres, and the excellent novellas, Ordinary

Love & Good Will, which both shine a flashlight on tender spots in

American culture.

There’s also Jane Hamilton, who wrote the novel A Map of the World, a scathing critique

of the prejudices and limitations of Middle America—in the world of that novel,

if you make one false move, you become an anathema.

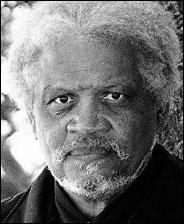

Ishmael Reed is a wonderful satirist who critiques American society with African American funk in mind in such novels as Mumbo Jumbo. Reed is also a poet, essayist, and playwright, one of the few writers who excels in all those genres.

Ishmael Reed is a wonderful satirist who critiques American society with African American funk in mind in such novels as Mumbo Jumbo. Reed is also a poet, essayist, and playwright, one of the few writers who excels in all those genres.

|

| Ishmael Reed, author of Mumbo Jumbo and many other books |

We

could add to the satirists John Kennedy Toole, who wrote A Confederacy of Dunces (a book I’ve never been able to finish, I

have to admit).

In

the nonfiction category, there’s Tom Wolfe, who pokes fun at the American

intelligentsia and other aspects of U.S. life in such books as Radical Chic & Mau-Mauing the Flak

Catchers and The Painted Word.

The

satirist or critic challenges the American mainstream. Unlike the populist

writer, he or she doesn’t see the U.S. experience as a source of wisdom or

epiphanies about the meaningful, small moments of everyday life. Critics and

satirists are taking aim at American society, often with either a humorous or reformist intent, but highlighting the sides of U.S. culture that are deserving

of scrutiny or even mockery.

Zack’s most recent book of poems, Irreverent Litanies

Zack’s most recent translation, Bérénice 1934–44: An Actress in Occupied Paris by Isabelle Stibbe

Other recent posts about writing topics:

How to Get Published

Getting the Most from Your Writing Workshop

How Not to Become a Literary Dropout

Putting Together a Book Manuscript

Working with a Writing Mentor

How to Deliver Your Message

Does the Muse Have a Cell Phone?

Why Write Poetry?

Poetic Forms: Introduction; The Sonnet, The Sestina, The Ghazal, The Tanka, The Villanelle

Praise and Lament

How to Be an American Writer

Writers and Collaboration

Types of Closure in Poetry